Number of investors flipping homes returns to precrisis levels; big banks get back in the game

Dec 28, 2016 By Kirsten Grind and Peter Rudegeair

House flipping, a potent symbol of the real-estate market’s excess in the run-up to the financial crisis, is once again becoming hot, fueled by a combination of skyrocketing home prices, venture-backed startups and Wall Street cash.

After nearly being felled by real-estate forays almost a decade ago, a number of banks are now arranging financing vehicles for house flippers, who aim to make a profit by buying and selling homes in a matter of months. The sector is small—participants say roughly several hundred million dollars in financing deals have been made in recent months—but is expected to keep growing.

In recent months, big banks, including Wells Fargo & Co., Goldman Sachs Group Inc. and J.P. Morgan Chase & Co. have started extending credit lines to companies that specialize in lending to home flippers. Earlier this month, J.P. Morgan agreed to lend an estimated $60 million to 5 Arch Funding, an Irvine, Calif., company that offers financing to flippers, according to people familiar with the deal.

“The floodgates have opened,” says Eduardo Axtle, a 35-year-old former telecom entrepreneur in Oakland, Calif., who has taken out about 50 home loans over the past five years. These days, he is bombarded by unsolicited emails from brokers offering him access to financing.

The number of investors who flipped a house in the first nine months of 2016 reached the highest level since 2007. About a third of the deals in the third quarter were financed with debt, a percentage not seen in eight years.

Trying to win business, big banks in the past few weeks have flown executives to Southern California—where much of the house-flipping activity is occurring—to organize funding deals, say people familiar with the meetings.

Investors are making an average profit of about $61,000 on each flip, up from about $19,000 at the bottom of the market in 2009, according to housing-research firm ATTOM Data Solutions, which is the parent company of real-estate website RealtyTrac. The calculation measures the difference between the housing value when an investor purchases the home and when it is sold.

The market for house-flipping loans in the U.S. is expected to reach about $48 billion in total sales volume this year, the highest since 2006, according to ATTOM.

That’s in part because home prices across the country are rising, reaching levels not seen since before the 2008 financial crisis. Housing also is in relatively short supply. Meanwhile, low interest rates and a surge in demand for homes from institutional buyers have also benefited house flippers.

Some borrowers and private lenders say investors have been offered debt in excess of the value of the home, also known as a high loan-to-value ratio. Others say some lenders are loosening up their documentation rules, requiring bank statements to get a loan, but not a W-2 tax earnings statement, for instance.

As these loans are made by relatively small finance companies and aren’t classified as owner-occupied loans, they don’t fall under many of the postcrisis rules written for banks and home mortgages. Some banks used to make these loans directly but now fund finance companies instead.

The boom is being accelerated by online lenders such as San Francisco-based LendingHome Corp. and Asset Avenue Inc. in Los Angeles, as well as crowdfunding websites such as Groundfloor Finance Inc., that allow individual investors to fund fix-and-flip loans. LendingHome, backed by venture-capital investors, says it has extended more than $1 billion in loans in the 2½ years since its launch.

Anchor Loans is one of the largest private lenders to house flippers. The Calabasas, Calif., company has received more than $220 million in new credit facilities, mostly from major banks, in 2016 alone, said Chief Executive Stephen Pollack, who declined to identify the banks.

After the financial crisis, a shortage of funding from large banks meant that Anchor had to turn away fix-and-flip business. This year, the company is on track to originate $1.1 billion in loans to real-estate investors, up from $713 million in 2015, Mr. Pollack says. “For the first time in our history, we actually have enough money to lend,” he says.

Loans to house flippers are short term—usually around seven months—and come with interest rates ranging between 7% and 12%. Because real-estate investors are typically higher risk, they put more cash down—sometimes as much as 65%. By comparison, a 30-year home mortgage has an interest rate around 4%, and borrowers typically don’t put more than 25% down.

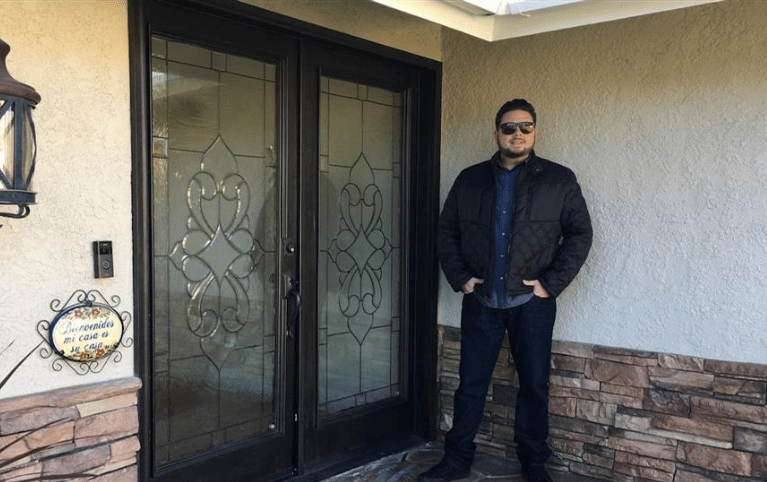

Over the past year, 37-year-old David Franco has collected profits of more than $200,000 on houses that he has quickly refurbished and resold, turning a hobby into an unexpectedly lucrative business. “There’s plenty of money to be made,” says Mr. Franco, who lives just outside of Los Angeles.

House-flipping television shows and training “schools” for new investors are proliferating. One “super-intense, hardcore” house-flipping boot camp in Bourne, Mass., promised to teach students about real-estate investing in three days to make “REALLY MASSIVE PROFITS,” according to marketing literature.

The increasing amount of speculative housing in recent months is “concerning,” ATTOM noted in a recent report. “We’re starting to see home flipping hit some milestones not seen since prior to the financial crisis.”

ATTOM said profit margins are getting squeezed in some markets. While house flippers typically aim to purchase a house at a 30% discount to the market, in some areas they’re buying homes at a 15% or 10% discount, said Senior Vice President Daren Blomquist. The research firm noted that the number of smaller, inexperienced house flippers entering the market is a sign of rising speculation.

George Geronsin, 36, a Southern California real-estate agent and house-flipper who has been in the business since 2008, said he recently sold the majority of the homes he was working on and is sitting on cash “until the next big correction” in the housing market.

“Anybody and everybody is getting into the business of house-flipping—that’s when you know it’s the end of the rope,” said Mr. Geronsin.

Investors in one large crowdfunding site, Realty Mogul Co., were interested in funding $1 billion in fix-and-flip loans through its marketplace, said Chief Executive Jilliene Helman. But the company decided to stop making such loans this summer because competition among lenders meant it couldn’t charge a high enough interest rate to make up for the risk.

Another question mark is the future of long-term interest rates. Since Donald Trump ’s surprise election victory, mortgage rates have been surging. If the trend continues, it is likely to chill housing markets, making it harder for investors to quickly flip homes for a profit.

There are only imprecise ways to measure home-flip default risks. The average foreclosure rate for loans secured by investment properties is 0.43% compared with 0.6% for loans on owner-occupied homes, but the foreclosure rate for investment property loans originated in 2016 is more than double owner-occupied homes, according to ATTOM.

Finance companies say their loans to home flippers are prudent. LendingHome, for example, says it limits its average loan size to reduce risk.

Big banks are offering lenders credit lines ranging from $5 million to $150 million, with interest rates between 3.5% and 6%, say the people familiar with the deals. The banks say they are shielded from major losses because their loan deals are backed by pools of securitized loans, sheltering them from a potential bankruptcy of the lender.

In the 5 Arch deal with J.P. Morgan, the bank securitized 150 5 Arch loans in a $60 million bond, and then lent out a portion of that amount back to 5 Arch in what operates like a credit line. The bank can also sell pieces of the resulting bond to other investors if it chooses.

Ahead of any funding deal, bankers say they are spending weeks reviewing the underwriting process that lenders use, making sure borrowers will be able to repay their loans.

This article originally appeared in the Wall Street Journal